Milan Mandarić was embarking on an entrepreneurial journey when he left socialist Yugoslavia, in addition to avoiding political scrutiny. He turned his family’s modest machine shop into a reputable industrial powerhouse in Serbia by the time he was 21 years old. However, under Tito’s rule, his success was so obvious that it led to his relocation, first to Switzerland and then to California, where the Silicon Valley boom was just getting started.

After arriving in the United States, he started Lika Corporation in the early 1970s, changing its focus from manufacturing floors to computer components. Lika rose to prominence as a major supplier of electronic components in a matter of years. Similar to seeing a flower in a field before it blooms, Mandarić showed the ability to recognize new tech needs. After that, he started Sanmina, which eventually merged and expanded to become Sanmina-SCI, a leading manufacturer of circuit boards worldwide. He was so good at seeing opportunities that he even got a contract from Apple in its early years.

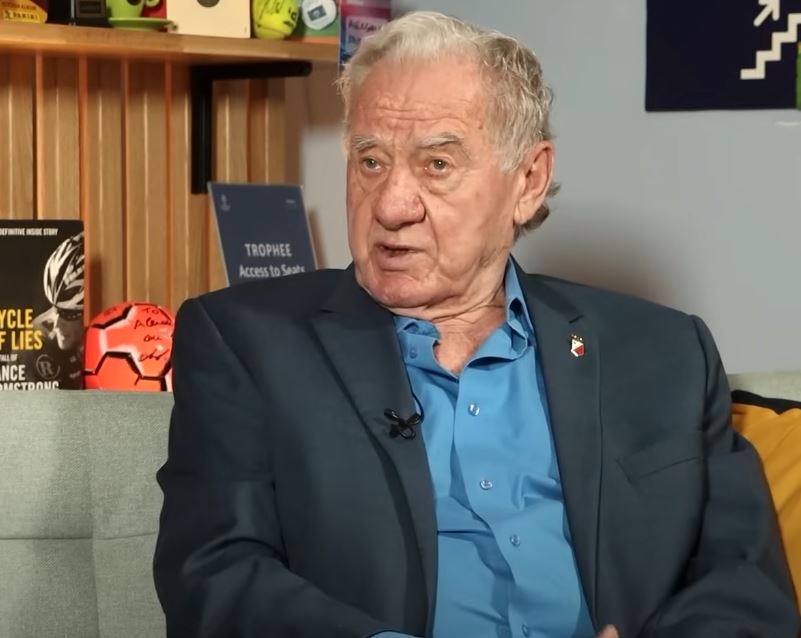

Milan Mandarić – Profile Overview

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Milan Mandarić |

| Birthdate | September 5, 1938 |

| Age (2025) | 86 |

| Nationality | Serbian–American |

| Birthplace | Gospić, Croatia |

| Tech Ventures | Lika Corporation; Sanmina (Merged to form Sanmina‑SCI) |

| Football Clubs Owned | Portsmouth FC; Leicester City; Sheffield Wednesday; Olimpija Ljubljana |

| Estimated Net Worth | £100 million (2025 estimate) |

| Reference | PAD Magazine (June 2025) |

Mandarić’s estimated £100 million net worth feels well-earned and noticeably diversified in recent days. It is proof of a methodical approach, not just accumulation. Long-term investments in football, real estate, and private equity were financed in part by his early tech endeavors. Despite being less ostentatious, these investments are incredibly dependable volatility hedges.

Although his transition to football may have seemed sudden, it was a natural fit for his disposition and style. He purchased struggling teams like Sheffield Wednesday, Leicester City, and Portsmouth FC and handled them like downstream companies in need of reorganization. A £40 million sale resulted from a £25 million investment at Leicester. He paid just £1 for a club that was heavily indebted at Sheffield Wednesday, rebuilt its finances, and sold it for £37.5 million. That is the private equity approach to sports, but Mandarić handled it with a calm composure that won over supporters.

His operating philosophy is particularly noteworthy: long-term over short-term gains; functional over flamboyant. While other club owners pursue high-profile player signings and branding deals, Mandarić concentrates on corporate governance, scouting, and stable infrastructures. He views supporters as stakeholders in the community and treats clubs like ecosystems. The fans respond well to that strategy because they see trust rather than a trophy-chasing speculator.

Even at the age of 86, Mandarić has continued to strategize in recent months. He is still the chair of Slovenian team Olimpija Ljubljana and has been connected to another English takeover. In football, where owners frequently burn out or chase publicity, that longevity is uncommon. That trap doesn’t seem to apply to Mandarić’s calm and straightforward style.

Behind the scenes, his real estate holdings in the US and Europe give his portfolio a layer of subdued stability. Stakes in venture and private equity, which are known for their inventive approaches to balancing risk and reward, have been financed by early tech returns.

His story is one of adaptation rather than just financial success. He dealt with socialism, being a refugee, the highs and lows of Silicon Valley, and the drama of football. His guiding principle in each arena was not impulse but structural investment. Even though his wealth is substantial, it is difficult to gauge its impact.